Overall Impact **** 4 stars Museum with excellent artefacts wonderfully displayed with thematic exhibits of Roman civil life

Roman Features ***** 5 stars Mosaics are many of the finest in Britannia, plus a lead coffin, wall paintings, a late antique horde of solidi and much more

Display **** 4 stars Thematic rooms work hard to bring the exhibits to life and explain how the inhabitants of Verulamium lived

Reconstruction **** 4 stars The restored rooms with wall paintings are superb

Access **** 4 stars Modern museum with good access. Car park handy for both Museum and Park.

Atmosphere *** 3 stars The Museum and Park are both branded Verulamium, but it is quite hard to visualise what the Roman city would have looked like: maybe some more illustrative boards around the park would help?

Other ***** 5 stars We reckon this is the second-best Roman museum in Britannia – and the best museum of civil life of the period. (We still have to give Vindolanda Museum the top spot!)

We were inspired by publishing our Brading Villa blog recently and, since the sun was shining, we thought we should have look at another Roman site. (Our first idea was Silchester and the finds in Reading Museum’s Roman galleries but, alas, Reading Museum is not open on Sundays. )

So our choice fell on Verulamium Museum and Park at St Albans. Thirty years ago we used to live in ‘Snorbans’ and a fine and distinctive city it is. Since then the old Museum – already good – has been refurbished, given a circular Roman-inspired entrance and had new galleries added. Thank you National Lottery Fund, once again!

Is this the best dedicated Roman museum in Britannia?

We think so – at least as far as civilian life is concerned (the latest incarnation of Vindolanda is simply stunning, obviously with a more military focus). Verulamium Museum sets out to be the museum of everyday Roman life and with dedicated galleries on trade and industry, life and death, and much else, it succeeds. Verulamium was the 3rd largest Roman city in Britannia (presumably after Londinium and Camulodunum?) and the quality of the finds excavated by Mortimer and Tessa Wheeler in the 30s and by Shepherd Frere in the 70s are tremendous. This thematic approach is quite commonplace these days but it’s carried through here with confidence and illustrated with some remarkable finds. Our favourites include:

1). The lead coffin from around 200AD from King Harry Lane with its scallop shell decoration and a rather witty video by the deceased (here wittily christened Postumus) describing his life and subsequent rediscovery.

2). The display of carpenters’ tools left behind while escaping the great fire of Verulamium in 180AD.

3). A tiny statuette of Mercury with his ram, tortoise and cockerel, and wearing a tiny torc.

4). The remarkable Sandridge Hoard of 156 gold solidi, found by a fortunate metal detectorist testing out his new equipment.

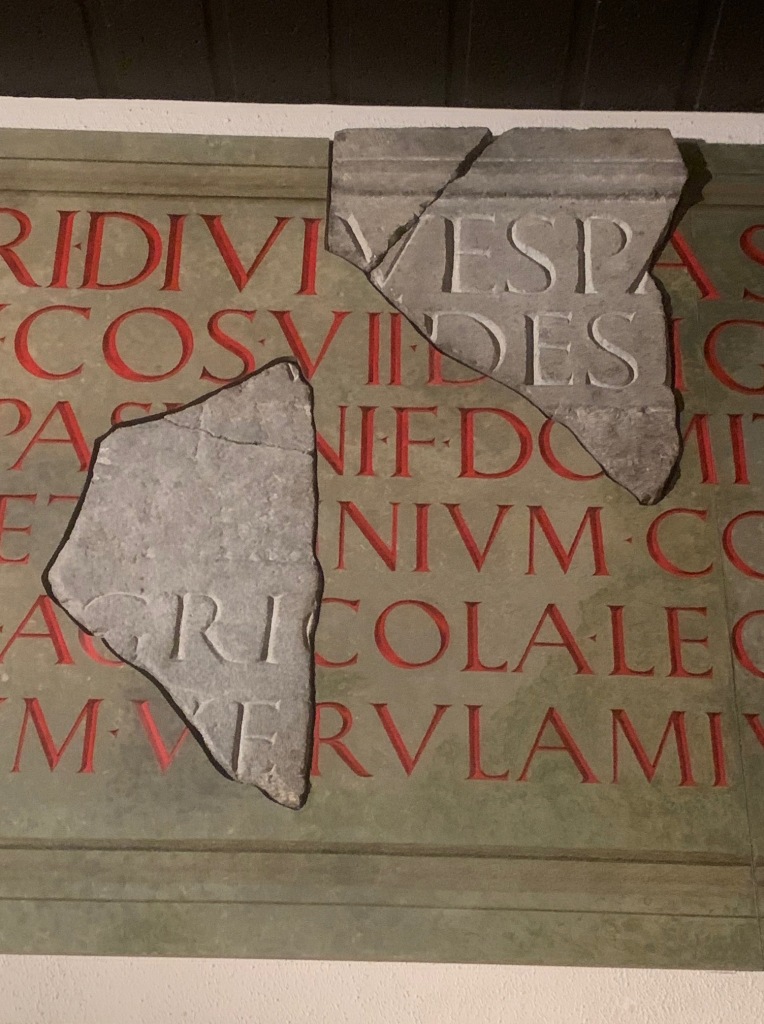

5). The inscription from the new Forum built in the reign of Titus which (most probably) mentions the Governor Julius Agricola, developing the pacified parts of the Province just as Tacitus describes.

This is before we have mentioned the real star exhibits of the Museum – the mosaics and the wall paintings from the fine mansions of the Roman city. There are 3 mosaics in the main museum hall – a shell image in the centre, with a horned figure (possibly identified with Cernunnos, a woodland god) to the right, and a lion and stag to the left.

The wall and ceiling paintings have been imaginatively displayed in reconstructed rooms, with the missing plaster and colours filled in. The overall effect is to give a real feeling of what a grand provincial mansion looked like. What strikes you are both the striking colours and compositions and the relative crudity of the actual workmanship – the representation of marble, for instance, is not at all convincing!

The first galleries cover pre-Roman Verulamion: the area was a centre of the Catuvellauni, who under Cassivellaunus led the resistance to Caesar in 55BC. Later the Catuvellauni were ruled by Tasciovanus and by 10AD Cunobelinus was in charge. He conquered the Trinovantes and moved his capital to the Colchester area, but continued to rule Verulamion. Whilst Cunobelinus successfully avoided Roman intervention, under his sons Caractacus and Togidubnus in 43 AD the kingdom was invaded by Claudius.

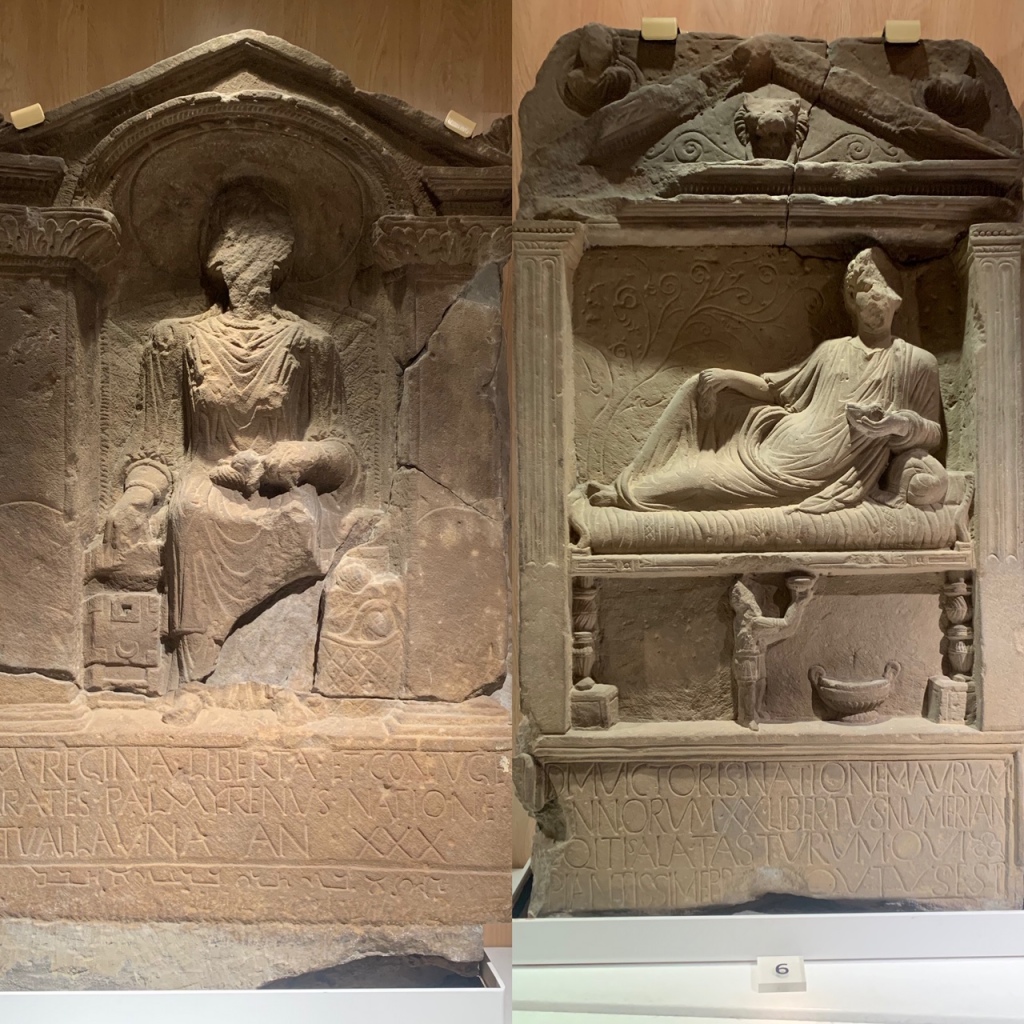

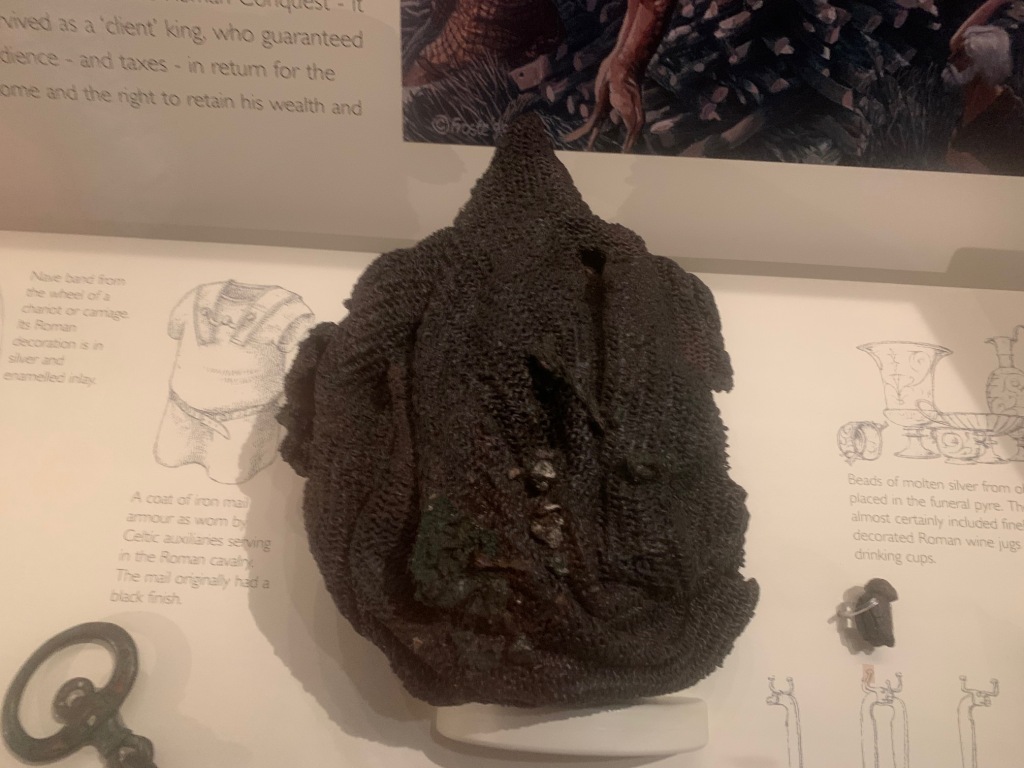

After the Roman conquest the Trinovantes were conquered and a Colonia of legionaries planted at Camulodunum. However, the Catuvellauni become a client kingdom, possibly under the leadership of Adminius, another son of Cunobelinus who had fled to Rome before the Conquest. The burial from Folly Lane dated to AD50 appears to be the leader of the Catuvellauni under Roman domination. The rich burial features a chariot, an iron mail coat (above) and quantities of silver, all placed on the funeral pyre.

The Museum sits close to the site of the vast Forum of Verulamium, on which the Church is built. So all round you are the hidden remains of the City. There are three things to see in the Park – the mosaic from one of the town houses, the battered remains of the City Walls and the site of the London Gate.