Overall *** 3 stars – a slice of a major fort, well set-out and explained, with a world-leading reconstruction

Roman features *** 3 stars – key buildings exposed, but much of fort sadly concealed, large Exercise Hall

Display *** 3 stars – good explanatory boards, replica statues and inscriptions, and a viewing platform

Reconstructions ***** 5 stars – the two-storey reconstructed barrack block really moves the debate forward!

Access *** 3 stars – access by sloping gravel paths, signs not multilingual

Atmosphere ***** 5 stars – for the barracks: really feel you were there (but could do with smells too!)

This latest post from our ‘Raetian Limes Adventure’ features the fort at Aalen. As noted in our previous blogpost, Aalen fort – as befits the base of the most important unit in the Province of Raetia – is the largest fort on the Raetian Limes at 6.07 ha. The largest Roman cavalry fort north of the Alps.

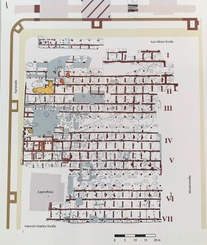

Unfortunately, the exposed part comprises only the central range but, given that this contains the HQ buildings, this alone is very interesting. The northern part of the fort was, alas, built over with housing in the 1920s and the southern part had already been filled by a cemetery.

There is a viewing platform above the exposed remains which gives you an excellent view of the HQ (principia), complete with a replica statue of xxxxx. On the path leading to this the Rotary Club of Aalen has thoughtfully provided replicas of some of the best stone finds from the Raetian Limes. There is a relief from a Mithraeum and a statue of the three Mother Goddesses.

The excavation of the principia was carried out by the Limes Commission before the First World War and has the limitations of the methods then available. Nevertheless the material finds, as exhibited in the Museum, are remarkable. Inscriptions to the Emperors start with Antoninus Pius, the date when the line of the Limes was moved forward in AD160. At that point the Ala II Flavia moved north from Heidenheim to Aalen where, curiously, they then constructed a complete replica of their previous fort just 30kms to the south! Aalen waw occupied until the collapse/evacuation of the Raetian Limes in AD254,

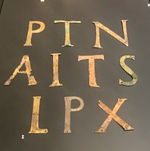

The principia was built on a massive scale (70m x 60m) to reflect the status of Ala II Flavia, with the typical suite of five rooms at the back where the remains of bronze statues of the Emperors were found (meticulously cut into minute pieces). There were also dedicatory altars and metal lettering from a lost inscription. The pride and grandeur of the unit really come across.

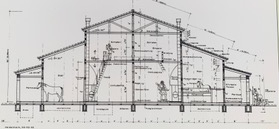

What we found most striking, though, is the enormous exercise hall calculated as being 18m high, for indoor training, briefings and displays.

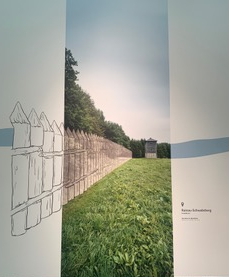

East of the Principia is a large building interpreted as a workshop, but the really stunning and revolutionary exhibit in the Aalen fort is the reconstruction of part of a cavalry barracks.

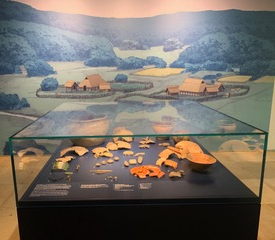

There were 12 double cavalry barracks, each with two squadrons (turmae) in the fort at Aalen, and the Museum here has rebuilt the end of one of them. What is so interesting is that it is a two-storey reconstruction, based on meticulous excavations from Ala II Flavia’s previous base at Heidenheim.

We find this two-storey configuration convincing. Depending on your view on the size of each cavalry turma in a 1000-person cavalry regiment (ala milliaria) there were between 800 and 1,000 troopers in the fort with as many horses and probably as many remounts, plus grooms and slaves. (Who mucked out the titanic amounts of horse dung from the 1,000-plus horses?) The idea that the well-paid troopers chose to live above the stables (not crammed into a small room behind them) works well from the point of view of space, cleanliness and warmth.

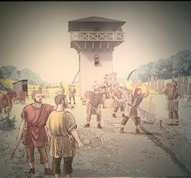

The techniques for multi-storey buildings were, of course, well understood by Roman architects and ground space was at a premium inside the fort walls.

The Aalen reconstructions are carried through magnificently with the front room of downstairs housing replicas of the small but sturdy cavalry horses, in a stable complete with Latin graffiti. The back room is treated as an arms store and office. Up a precipitous stepladder is the sleeping room (which visitors sadly can’t access).

If this was the format of cavalry barracks at Aalen then we should surely expect to find them in other cavalry forts around the Empire, for instance at Chesters on Hadrian’s Wall. Indeed, Historic England is now suggesting that the barracks exposed by excavations there were probably two-storey too.