Overall: **** 4 stars – another excellent German Limes museum, focusing on the Raetian Limes and with outstanding finds. (Do this and Weißenburg.)

Roman features: **** 4 stars – superb collection of artefacts from Aalen and related sites.

Display – ***** 5 stars – brand-new museum displays, chock-full of interesting material with effective interpretative panels in German and English.

Reconstructions – N/A – but seethe wonderful cavalry barracks and adjacent fort site (see later blog).

Access – **** – 4 stars. Car parking outside (or on street), good access within building, bilingual displays, small friendly shop.

Atmosphere – ** 2 stars. Lively and well-attended but not strongly atmospheric.

On the Sunday after our visit to Weißenburg Museum, ever-enthusiastic gluttons for (Roman) punishment, we visited the Limesmuseum Aalen…

You are probably way ahead of us in realising that the name Aalen reflects its origin as the fort of Ala II Flavia, the premier unit in the Roman Province of Raetia. An Ala Milliaria was a 1,000 trooper strong cavalry unit, probably with twice as many remount steeds. There were only eight of these in the entire Empire, and the officers and troopers were all paid more than their equivalents in the mighty Legions. So Aalen was a very important place from AD160 to 260, when the Raetian Limes collapsed. Much later it regained its importance as a Free Imperial City in Eastern Baden-Württemberg.

The Museum

There has been a museum devoted to Roman Aalen and the Raetian Limes since 1964, and we have visited it twice before. It has just been upgraded (May 2019) by Baden-Württemberg, assisted by the local authorities and the Deutsche Limes Kommission (DLK). It’s fantastic to see the authorities both valuing their local heritage and seeing the tourist potential. There is an enormous flow of tourists in the summer ‘doing’ the Limes trails on foot and by bike. The Museum contains the best finds from the Baden-Württemberg section of the Raetian Limes.

The ambition of the new museum is large – it starts by setting the context of Roman imperialism with a forest of portrait busts (reproductions) of Emperors and their families. This provides as suitably awe-inspiring start. You then see a magnificent statue (another repro) of Trajan. Why Trajan? Well, the latest dating of the first version of the Lines is ‘early Trajanic’.

There is a typically confident statement about the purpose of the Limes:

“The Limes, however, was neither a military defensive position, nor a border in the modern sense, but a control line. From here Rome observed the movement of people and goods into its territory”.

One could argue for a long time about the purpose(s) of the Limes (defence, attack, control, customs etc) – but we think this is a pretty good start.

You then have a choice of route, since the Museum is a large square with a smaller square room inside it. We chose to go round the outside where there are areas devoted to themes in a logical sequence.

The Raetian Limes were only occupied around AD105-264: compare this 160 year span to the 340 years that the Hadrian’s Wall was occupied! Another remarkable difference from the British ‘Limes’ is that there was little population in Raetia and the Upper Danube area before the Roman occupation, whereas everywhere that has been examined beneath Hadrian’s Wall has shown traces of ploughing before construction bega

In the Roman Army, the Cavalry were, contrary to received wisdom, the real elite units in the Provinces: a Trooper (Eques) was paid 2,800 sestertii a year under Septimius Severus, compared with a Legionary (Miles Legionis) who received 2,400.

The civil settlement (vicus) was the home of many immigrants from across the Empire, drawn by the wealth of the troopers and the opportunity for trade. There are interesting statistics on the food consumption of the 1,000 Troopers in the Ala Flavia, a neglected aspect of the impact of the Roman Army in most museums.

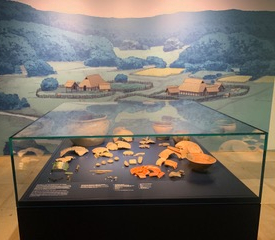

There are some amazing finds from the massive HQ (Principia) of Aalen including lettering from inscriptions and tiny cut-up pieces of what were once bronze statues of Emperors.

There is also a CV (cursus honorem) for one of the Ala Commanders which brings home how the Army managed the top talent serving on the Wall in Britain as in Raetia, Africa and in Rome. And finally, a striking display of 5 sports helmets (even beating Weißenburg’s 3!)

To anyone interested in the Roman army, and the cavalry especially, this is a fabulous display of treasures, done in an informative and spacious way. To our minds, one of the cleverest elements in each room are the wall-height recreations of what the places being described actually looked like. All done very accurately – the only minor niggle is the unlikely cleanliness of the roads in the vicus of a cavalry fort (see above), with thousands of horses – let alone all the pack animals…

After all this brilliance, the room in the centre is something of a disappointment, at least to us (although we know some visitors really like it). It aims to bring the life of the garrison, the vicus and the area to life by audio-visual.

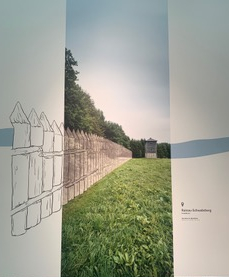

Next, you go upstairs where there is an exhibit on the Raetian Limes in a beautiful large white-painted room with a central courtyard open to the sky. Around the walls are almost life-sized photographs of the Limes sites today flanked by line recreations of what they looked like originally. This, in our view, works brilliantly well.

What works less well is a touchscreen map with coloured lights showing the way the Roman Frontier in Upper Germany and Raetia (now Baden-Württenberg and Bayern) has evolved: it had already broken, as museum technology often does.

Finally, there are some remarkable remains from a well into which an innkeeper had lowered his complete set of working materials when the Frontier collapsed. Cauldrons, containers and all were found in the remains of a net, hidden so that he would be able to retrieve them on his return after the Limes were restored. But they remained there until archaeologists found them in the modern era…