Overall Impact **** 4 stars – Housesteads has ‘star quality’, given its position atop the crags and on a slope that faces you as you approach.

Access ** 2 stars – it’s a long trudge up from the National Trust carpark, although it provides spectacular views of the fort in its context (although disabled parking at the top of the hill can be arranged at the information centre for those who require it). It can be windy and uneven underfoot.

Atmosphere ***** 5 stars – it’s not difficult to imagine you are a one of the Tungrian soldiers stationed there, gazing out into the drizzle to spot raiders or smugglers!

Other ** 2 stars – the famous latrine provides a good source of lavatorial humour for children of all ages!

For many people, Housesteads is the quintessential Roman auxiliary fort and it is definitely ‘the fort to see’ on Hadrian’s Wall. However, as always, when you dig into things with the Roman Army, it’s not quite that simple…

Housesteads was one of the forts built as a result of the ‘Fort Decision’ in around AD124 when the Roman High Command decided that – instead of a thinly-held ‘curtain’ along the new frontier with turrets and milecastles communicating with forts in the rear along the Stanegate Road – it was necessary to man the border with troops of all kinds, ready to be deployed forward aggressively. At the same time, probably, the decision was taken to narrow the wall from a massive 10ft to 6ft. Wall expert David Breeze estimates that troops on the front line increased from c3,750 to c11,000.

Part of that deployment was the deployment of a thousand-strong infantry cohort (Cohors Peditata Milliaria) to Housesteads. This involved the knocking down of a part-constructed turret which can be seen in the northern part of the fort, outside the granaries and just inside the fort wall which was then pushed as far towards the edge of the cliffs as possible, making the North Gate meaningless and purely decorative. But they still built it – after all, this is the Roman Army!

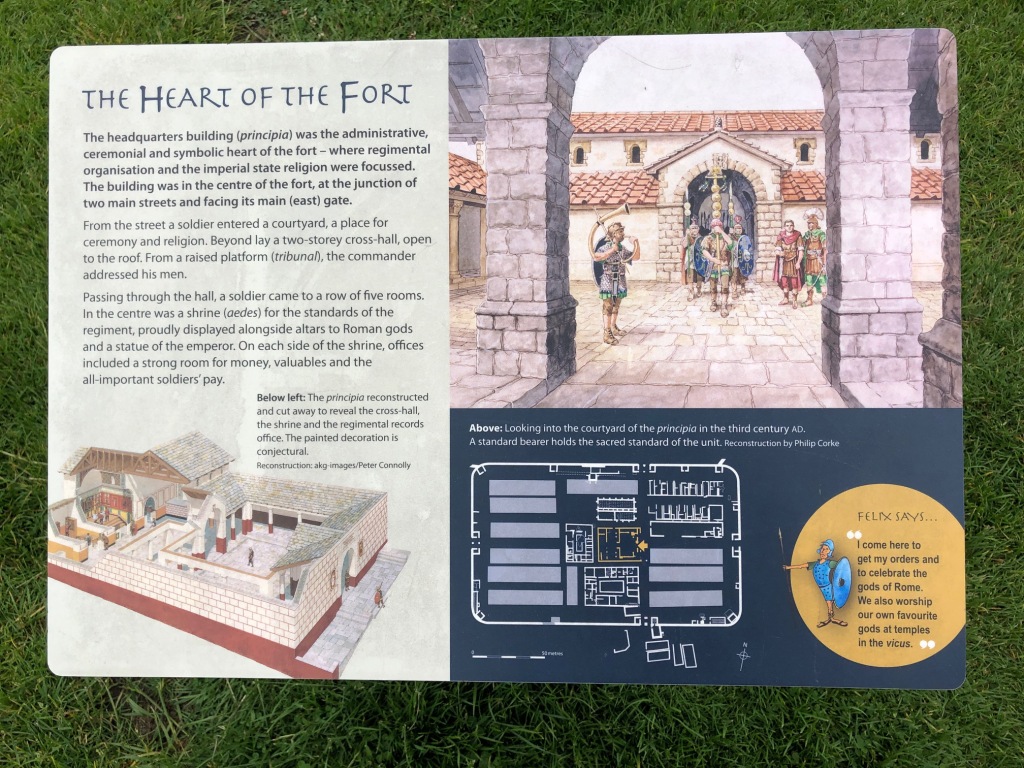

Since it contained 10 centuries of 80 men each (800 in total), the fort is larger than normal at 2.2 hectares. There were 10 infantry barrack blocks: 5 west of the central range and 5 east, each row containing an additional workshop building. In the central range, stood the usual HQ (Principia), this time facing east along the long axis, with two substantial granaries to the north, and a magnificent house (Praetorium) for the Commander and his family, with a Hospital behind. All of these were built on a steeply sloping site, exposed to the frequent wind and rain of the Northumberland weather. So the ‘poor bloody infantry’ got Housesteads Crags, whilst the better-paid elite cavalry got the bucolic pleasures of Chesters in the North Tyne Valley.

We don’t know which unit was lucky enough to get this windy posting: clearly being ready at short notice to deploy aggressively north of the Wall was vital – why else put them here? However, along with the rest of the Wall, all this site was dismantled or moth-balled after Hadrian’s death in AD138, and Antoninus Pius’ decision to move the frontier forward to the Clyde-Forth Isthmus and to what become the Antonine Wall. So could we look on the 50 years of Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus from AD117 to 167 – far from being the Golden Age of the Roman Army – as being instead an era at least of indecision and waste of effort, or even of failure?

When the Army came back to the Wall in the early AD160s, the Housesterads garrison was the Cohors I Tungrorum which by now had a complement of 800 infantry. Originally recruited as auxiliaries from the native Tungri of Belgica, they had been stationed at Vindolanda in the late 1st Century, and by the AD180s would have become thoroughly local on the Wall. They were augmented by barbarian irregular infantry from ‘free’ Germany (Numerus Hnaudfridi) and cavalry from Frisia (Cuneus Frisiorum), presumably recruited to provide a certain ‘barbaric’ edge to the Tungrians’ regular tactics.

Amazingly, the Tungrians were still there at Housesteads by the time of the Notitia Dignitatum in the late 4th Century. However, by then the neat barrack blocks had been divided up into what have been somewhat weirdly named ‘chalets’, one replacing each previous set of contubernia rooms. Some people think this reflects the decline of the Roman Army, with families moving into the ‘chalets’ along with the soldiers. But at Housesteads there is very little evidence for this happening (unlike at Vindolanda), so the reason for the rebuild remains unclear.

Visiting the Site

You stand a good chance at Housesteads of being blown away, drenched or at best slightly dampened by the Gods of the Northumbrian Weather. However, there is plenty exposed on the site from different periods which is well worth seeing.

The best plan is to visit the Museum (housed in the old farm buildings) on your way onto the site. Here are some key finds from the fort plus a really good model of the fort as it was built in the AD120s and some excellent pictorial reconstructions of the whole fort and its key buildings. What is most striking is how the Roman architects did not let the sloping nature of the site get in the way of laying out the regulation plan; and how much effort was put into constructing a multi-storey Commander’s House with a central courtyard – great in the Mediterranean but probably a source of flooding up here.

It is worth then visiting the (pointless) North Gate to look over into the Barbarian lands and a view for miles north, and to gaze west and east along the Wall that bestrides the crags. And in the north-east quadrant you can see the ‘chalets’ laid out in their irregular plans.

As a final treat, everyone visits the south-east corner to marvel at the Roman latrines, which were flushed by the plentiful rainfall at Housesteads. Apparently, though, the plumbing is not so clever and effective as it looks…