We visited Tarragona just after the New Year when there were no crowds; it was chilly but with warming sunshine.

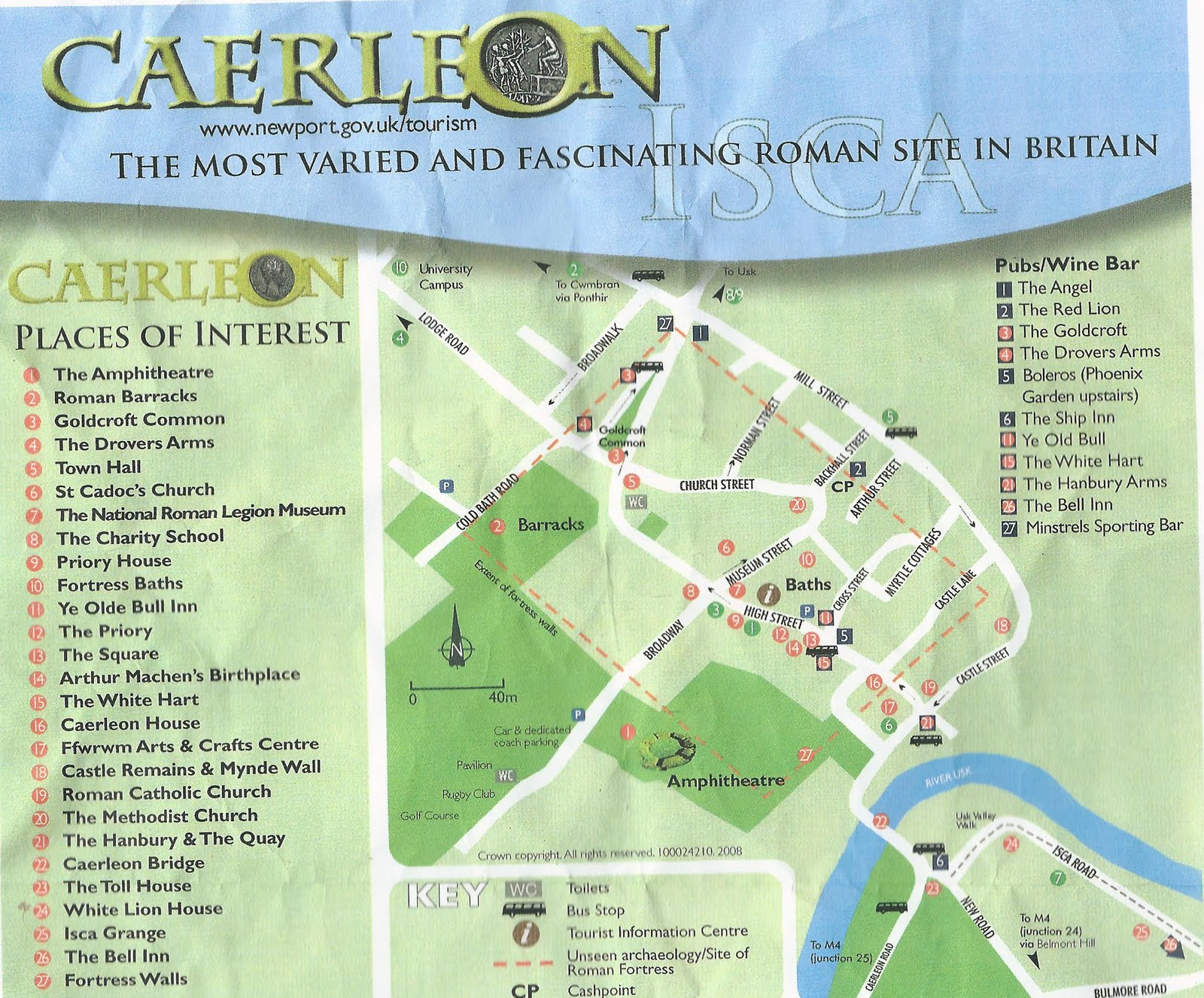

If you are coming from Barcelona, come off the toll motorway AP7 onto the A7 and then the A340, so you can enter Tarragona along the course of the ancient long-distance road, the Via Augusta. It is pleasing to see the city’s Roman name still celebrated today, with a large Tarraco sign at a roundabout.

Another advantage of this route is that you pass the Tower of the Scipios, a late First-Century BC funerary monument. Nothing to do with the Roman family of the Scipios themselves, but a striking survival and a taste of things to come!

Brief History of Tarraco

Tarraco was probably an Iberian settlement before its fortification by the brothers Gnaius Cornelius and Publius Scipio in 217BC at the start of the Second Punic War, and building of a military port – Tarraco Scipionum opus, as Pliny the Elder says.

It was Scipio Africanus’ base from 211 – 210BC, where he met the Iberian tribes in conventus. During the long conquest of Hispania, Tarraco remained a supply base for the Roman military and capital of Hispania Citerior. It became a Roman Colony around 45BC after Caesar’s victory at Munda in the Civil War, so added Iulia to its name.

Augustus resided in Tarraco in 27BC whilst overseeing the completion of the conquest and he reorganised the Provinces, Hispania Citerior becoming Hispania Tarraconensis, with about two-thirds of the land area of the Iberian Peninsula ruled from Tarraco. As befits a major provincial capital Tarraco prospered and a theatre was built. The trans-Peninsular road was restored as the Via Augusta and a Temple to the Deified Augustus was erected in 15AD after his death.

Vespasian, as in Britain, was a keen organiser of and investor in the Provinces. After his victory in the Civil War of AD69 he addressed Hispania, with Latin citizenship being granted to its inhabitants and the former tribal areas, and cities re-organised into areas focused around urban centres – both colonies and municipalities. This required the establishment of the Provinciae Concilium as a centre of Roman and Hispanic pride.

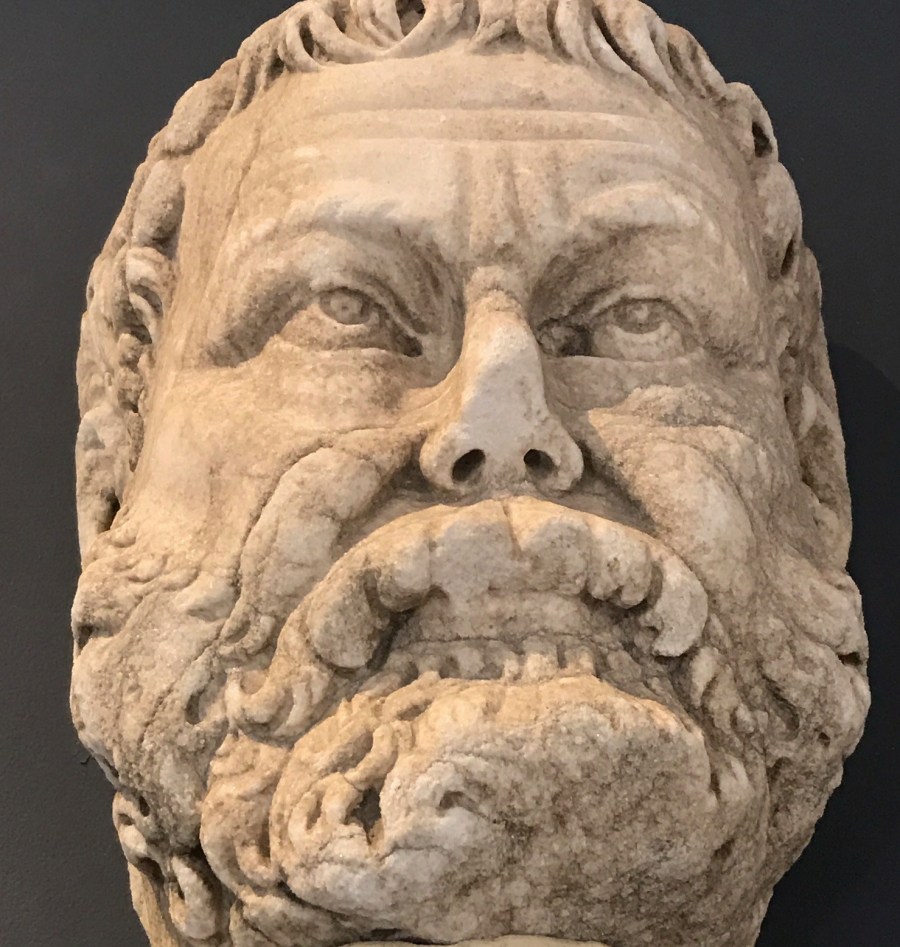

Inscriptions to Flamines and Flaminicae – priests and priestesses of the Provincial and Imperial Cult – have been found: these two are dedicated to Flaminicae from the Second Century AD?.

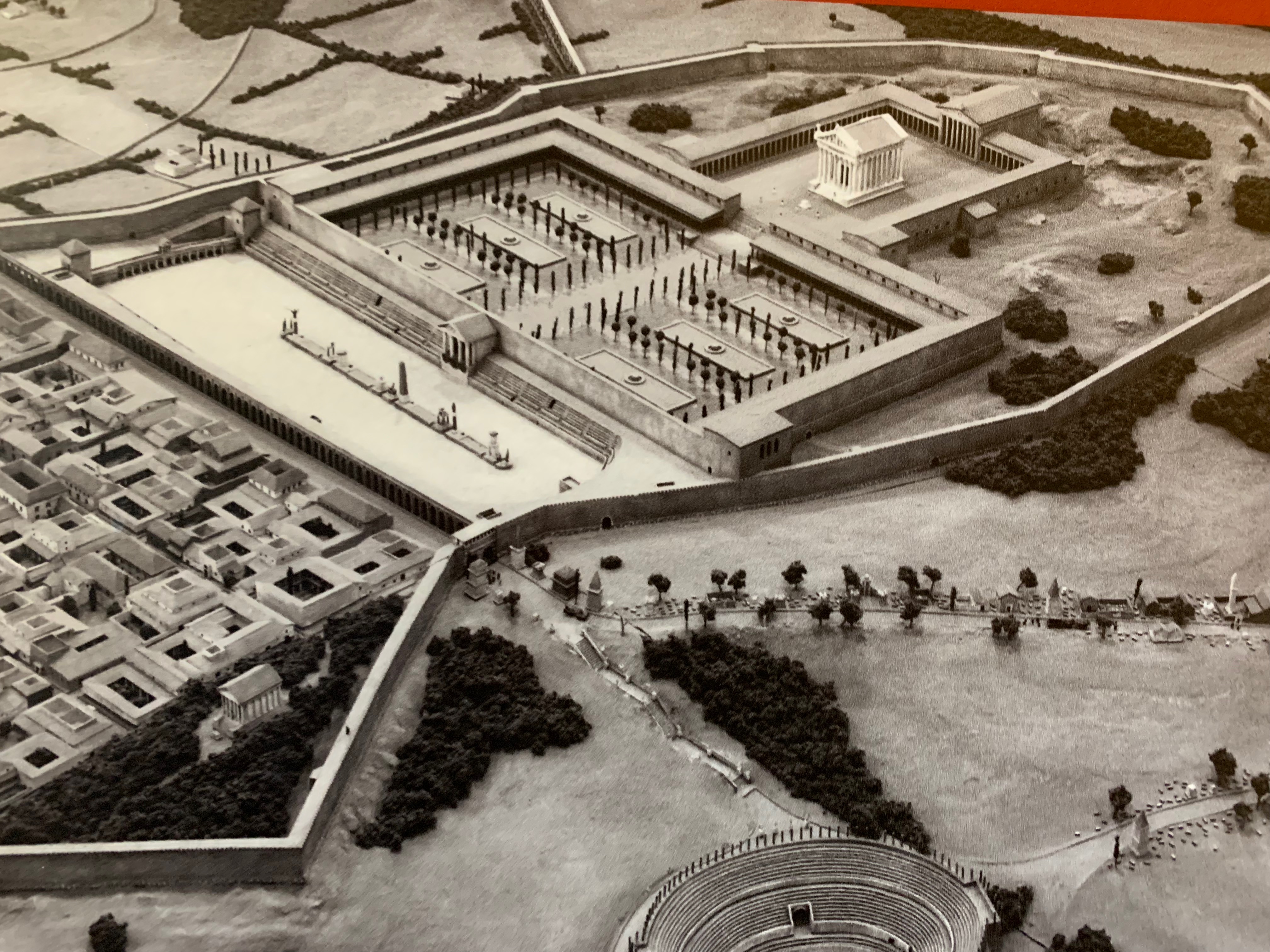

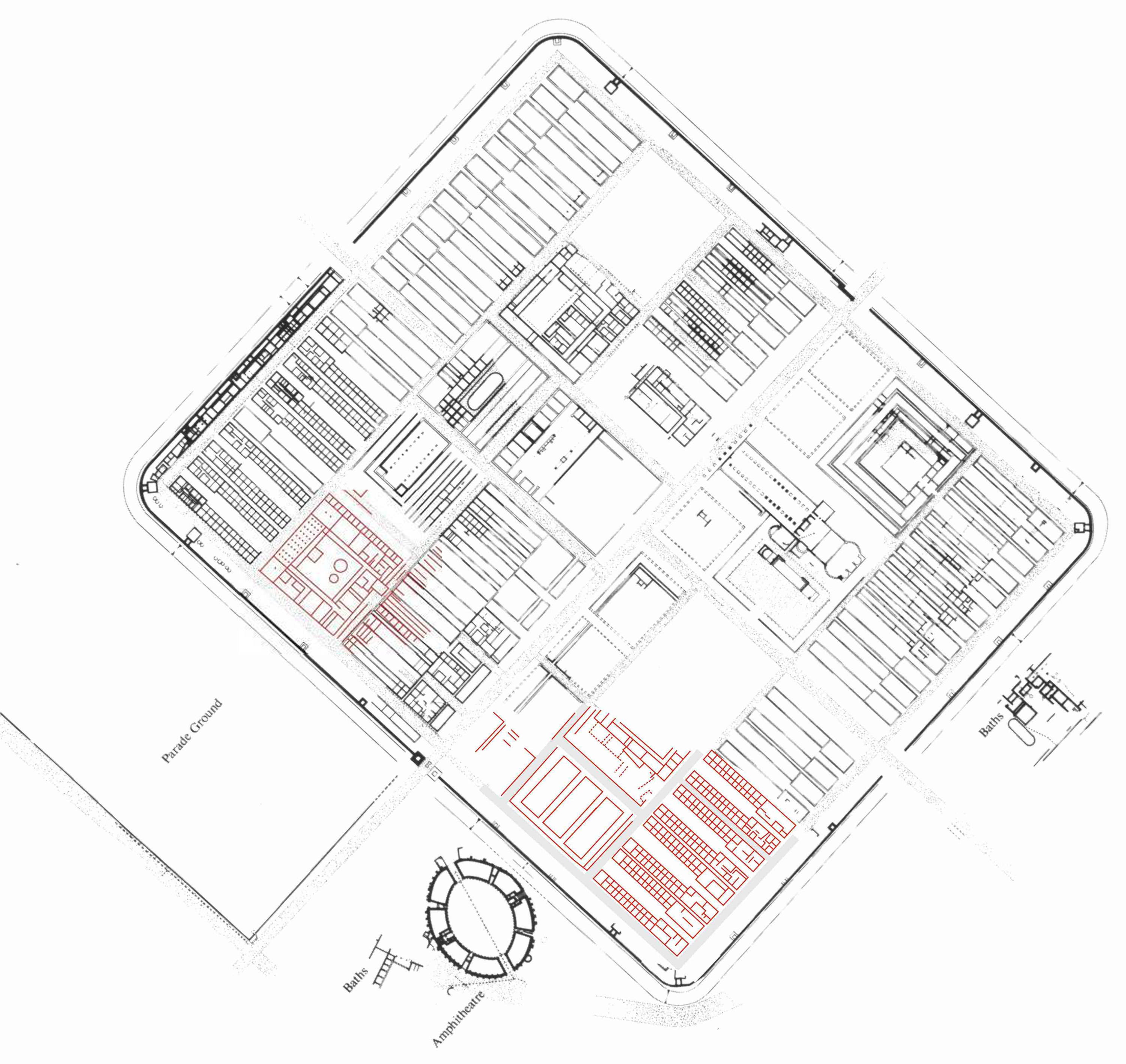

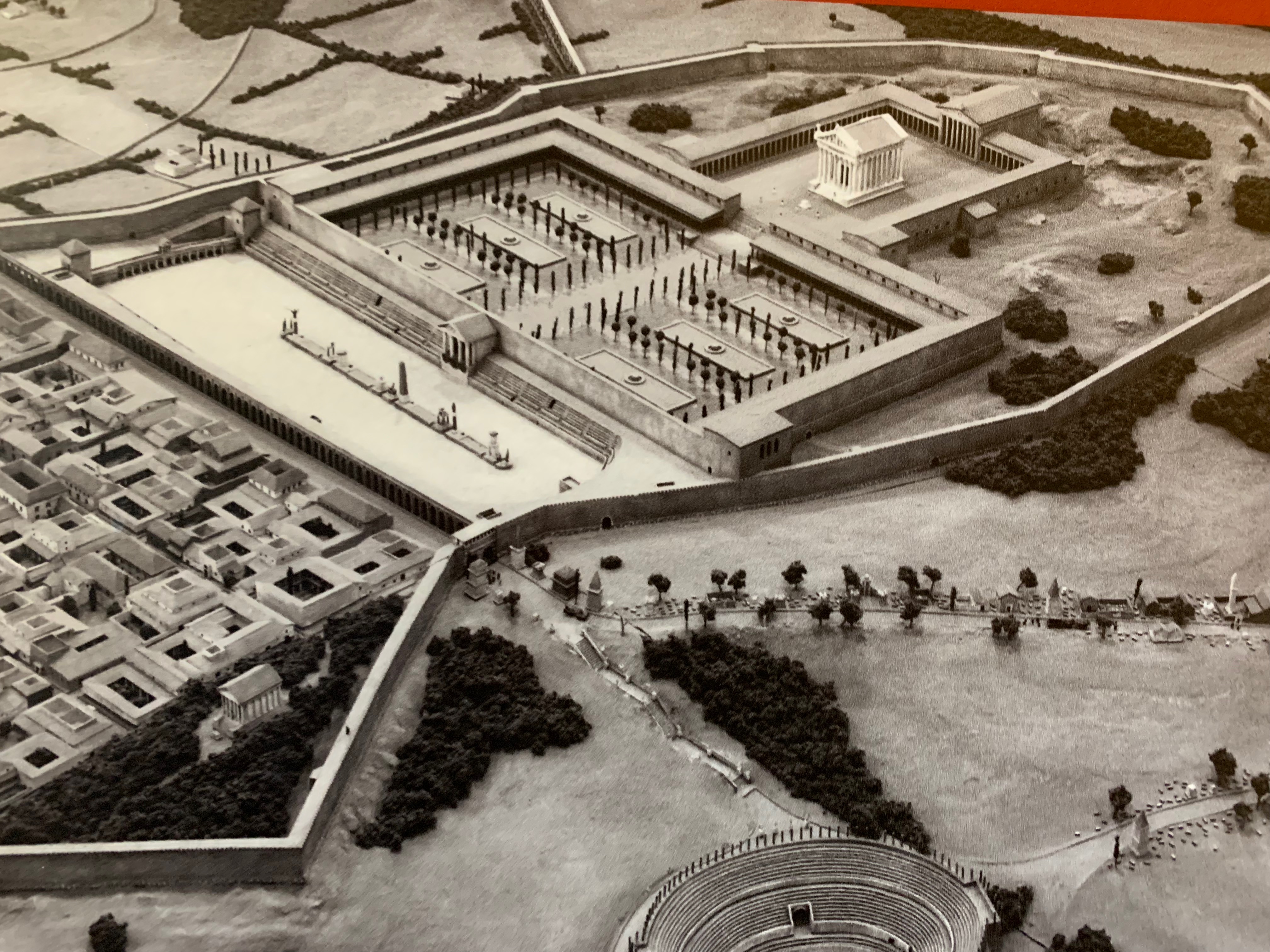

Tarraco, as befitted the provincial capital, received a whole new urban quarter with a provincial Forum for the administration, a Temple to the Imperial Cult and subsequently a Circus – see the model above.

Following this Tarraco prospered for 150 years but, along with the much of Roman Gaul and Spain, the city declined in the Third Century AD and was merely one of six provincial capitals under Diocletian. It was occupied by the Visigoths in 476 and by the Muslims in 713.

The Remains

The Roman Remains of Tarraco are deservedly a UNESCO World Heritage Site. For the visitor they consist of three areas:

- the original lower town around the port with its own ‘colonial forum’ and theatre

- the upper town, probably occupied by military installations in the Republican Period but developed as the Provincial Centre under Vespasian and Domitian, with Temple, Provincial Forum and Administration, and Circus.

- sites outside the city including an Aqueduct, Arch and roadside funerary monument.

The Circus

Entering by the Via Augusta you arrive in the centre of the old City, to be confronted on your right by medieval walls built around the Roman Circus. Try and find the nearest car park (helpfully signed), which is conveniently situated under the Placa de la Font with the Ajuntament (City Hall) at its end. This long rectangular space occupies more than a quarter of the former Circus. Walk from the Placa towards the Sea and you will find the remains of the curved end of the Circus.

The Circus was 290m long and 65m wide, and was part of the major investment in Tarraco as the Provincial Capital of a re-organised Hispania under Vespasian, with the work probably completed under Domitian. The site is well displayed and, although converted into fortifications in the Middle Ages and partly blown up in the French Siege of 1811, provides a good impression of what the Circus looked like. The Tarragona authorities have invested in digital tools and you can download a free location-based App that enables you to visualise the Circus and other key sites in Roman times. All you need to do is to download it onto your phone then scan the bar codes at the sites.

The key remains of the Circus are the remaining tunnels under the curving end of the course and for some way under part of the former seating on the north side of the Circus.

The Temple of Augustus

Remarkably, the walls of the temenos (the sacred enclosure) are preserved in the buildings around the Cathedral Cloisters, now the Cathedral Museum – see above. Unsurprisingly, the 12th-Century Cathedral occupies the same site as the Temple of Augustus, at the highest point of the hill above Tarraco.

The Provincial Forum

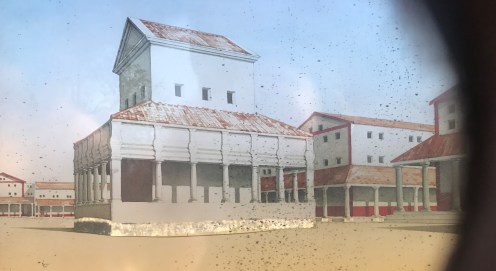

It was started in 73AD under Vespasian and was situated up the hill from the original settlement. It is thought to have consisted of buildings for the Provincial Council (see above), a Curia (senate house), an Audience Hall for the Governor and the Temple of Augustus, plus offices for the provincial financial administration and archives.

The Amphitheatre

Given that gladiatorial combats had to take place outside the walls, Tarraco‘s Amphitheatre was situated towards the sea, and can be viewed well from the top of the Roman and Medieval tower termed the Praetorium. It was built at the end of 1st Century BC, presumably when Tarraco became a Colony for Civil War veterans who liked and could afford such entertainments. It is estimated that it could hold 15,000 spectators.

Having been through many vicissitudes over the millennia, as a prison, a convent and so forth, the seating on the sea-side is still there but the central arena, as so often, is cut by the under-surface corridors and remains of later buildings which spoils the effect somewhat. This means that modern gladiatorial reconstructions are restricted to a quarter of the original surface area.

The Colonial Forum

Down the hill in the main town lie the remains of Forum of the Colony as opposed to the Province. There is a reconstructed column, which you often find in excavated forums (see Thessaloniki) and a few arches – a site for the completists.

The Theatre

Taking advantage of the slope down to the port, under Augustus the Roman Theatre was built facing the port. There is a viewing platform where the key remains can be seen, including some surviving seating and the foundations of the scaena. However, it’s not Merida!

Walls of Tarraco

The Walls are, as with so many sites where there has been continuity of occupation (Exeter in Britain has similar layers), a confusing mixture of pre-Roman, Roman, late Roman, Muslim and Medieval additions. However, it is claimed that the circuit of the old Quarter for over 1km are fundamentally Roman and there is a pleasant promenade – the Passeig Archeologic – from which they can be viewed.

Ferreres Aquaduct

The Aqueduct is located 4km north of the city and brought water from the River Francoli 15kms north of Tarraco. It is thought to date from Augustus’s time in the City and is composed of two imposing levels of arches, with a maximum height of 27m and a remarkable length of 249m.

Tower of the Scipios

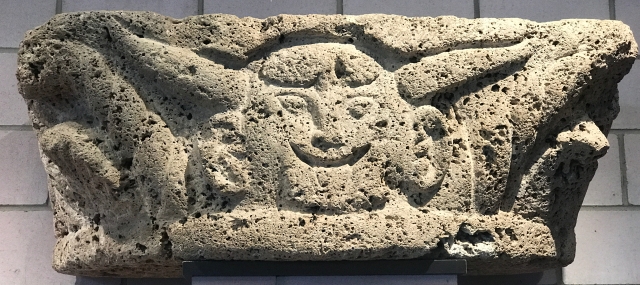

This is a a funerary monument situated on the Via Augusta 6km east of Tarraco. It is decorated with two reliefs – now much weathered – of the god Attis, deity of death and resurrection. For years these were identified as the Scipio brothers, founders of Roman Tarraco.

Triumphal Arch of Bera

A further 15kns NE of the Tower of the Scipios along the Via Augusta is the Arch of Bera. It was erected, as its inscription informs us, because of a bequest by Lucius Licinius Sura in 13BC, and is thought to be dedicated to Augustus and to mark the limit of the Colony of Tarraco.

Tarraco in Summary

As can be seen from the descriptions above, none of the surviving remains is, individually, the best or (with the exception of the Aqueduct) even nearly the best in the Empire. However, like one of your best creations in the wonderful game ‘Caesar III’, Tarraco has one of everything that matters – Amphitheatre, Theatre, Circus, Walls, Temple of Augustus and so forth. It is also very well displayed and the citizens of Tarragona are clearly proud of their Roman heritage: a lot of effort has gone into their digital support to try and bring the ruins to life. So it is well worth a visit.

Top Tips

The Archaeological Museum is at present closed for renovations. It was reputedly excellent. Avoid Sundays and Mondays when many of the sites are closed!

Tarraco – A Confession

We visited as a family with a toddler which meant that we could not in the time available, having driven down from Barcelona, visit all the sites ourselves. Although we saw the main ones, as the photos prove, we have had to cover some of the others from online sources. We wanted to do this so we could publish this blog and encourage Roman enthusiasts to visit this delightful and fascinating City that really values its Roman Heritage.

41.118883

1.244491